Customer Centricity is not a marketing communication issue, but a comprehensive business approach. This naturally includes customer-centric products. Products that are developed in such a way that they are loved by the targeted customers. This is through customer-centric thinking and working in product development, management & marketing.

In the last few articles, we have explained how to find the most valuable customers, how to collect structured information about these customers, and how to put this information into usable „chunks“ such as personas or customer journey maps. In this article, we want to pick up where we left off and show how insights can be used to develop customer-centric products.

If we have done our customer research homework well, then the first step in the product development process is almost done: determining the „problem space”. This is where we first determine which customer group we want to address, which problem of these customers we want to solve, or which job we want to help them with. So, everything starts with the customer.

In the problem space, we start the ideation process: developing solutions to the customer’s problem.

This contrasts with product-centric companies, which often start with the following questions: „What additional products can we develop based on our competencies?“, „What features can we integrate?“ or „What technology can we use to develop new products?“. The danger of such an approach is, that product development misses the customer’s need and thus is no success in the market.

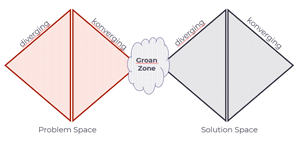

A helpful image for the approach to customer-centric solution/ product development is the „Double Diamond“ (see Figure 1).

One way to complete the first step – to expand the problem space – is to expose yourself to the user’s problem. In other words, you slip into their shoes and experience the problem firsthand. This solution has some advantages, because it is just not so much focused on a problem described by the customer or the product, but on the comprehensive experience that is made in the context. This broader perspective allows us to look at other problems that may exist and allows us to understand the background of the problem mentioned.

What we mean exactly by this is illustrated by this brief example:

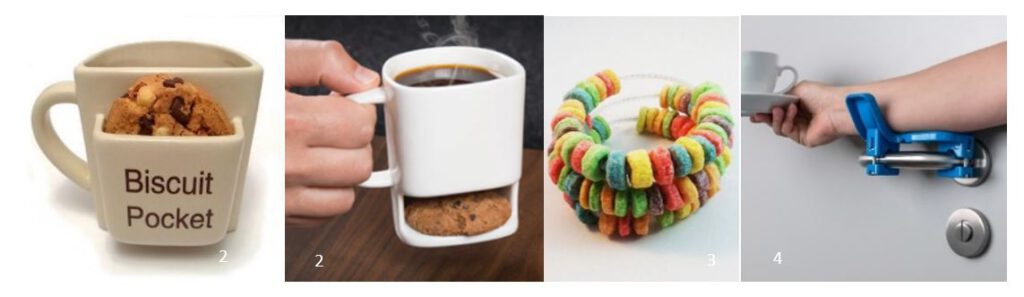

The customer reports his problem: „Whenever I have cookies in my hand in addition to my coffee cup, I can’t manage to open my office door. I should actually be able to hold both in one hand.“ If we jump right into finding solutions, we will probably develop solutions for how best to place the cookie in or on the coffee cup. In doing so, we „listen“ to the customer who says they need to be able to hold BOTH in one hand. We stay very narrowly in the Problem Space and thus focus on a very narrow Solution Space. But if we put ourselves in the shoes of the user, and include the environment, we see many other aspects of the problem: the door, the colleagues, the clothes, the cookie itself, or the walk through the office. So, we see other possible starting points for a solution that could lead to completely different, and possibly much more appropriate, profitable, sustainable products (e.g., door automation, different door handles, crumb-resistant jacket pockets, cookies to wear around your neck, delivery service at the workplace, and so on).

Other methods, that are suitable for expanding the problem space include customer observation, customer research (experiments), in-depth interviews, or open collaboration with the customer.

In the second step, we must meaningfully reduce (converge) the broad solution space again.

How do we extract the supposedly most important problem?

We do this by consolidating, refining, prioritizing, and evaluating the problems in terms of their importance, relevance, and urgency to the customer/ user with the knowledge we have already gained about the users. We test our assumptions that this problem is relevant and urgent with hypotheses using the same logic as we test hypotheses for solutions.

Of course, this transition from problem space to solution space is not linear, as it may seem here. Rather, in practice, there is often a back and forth until one has identified the relevant problem space and starting point for solutions (often called the „groan zone“).

The identified, most important problem to be solved is now formulated in an adequate (brainstorming) question. The question should limit the solution space to the right extent, neither too narrow nor too broad (e.g. „develop a tool for storing relevant thoughts that is as easy to use as possible“). The solution approach should not be included (not: „develop a writing tool that is easy to use“) but constrain the solution finding to a reasonable extent (not: „find a solution for storing all our thoughts.“).

The well-formulated question is the starting point for the third step: idea generation.

First of all, divergence is again used, i.e. the solution space is opened as broadly as possible. Change of perspective, diverse teams, use of diverse creative/ brainstorming techniques support divergent thinking. In this phase, criticism of ideas, a lack of creative freedom, or too tight a time or quantity restriction on idea generation are to be urgently avoided. The motto is „anything goes“! The first phase starts open-ended and allows a large field of ideas.

Only in the fourth step ideas are reduced (converged) back to meaningful approaches and the basis to products that are loved.

First, we structure the ideas into meaningful clusters (e.g., by time or technical feasibility, by degree of innovation, by business approach, by fit to our own core business, or the like). The team then evaluates the ideas in terms of their fit to the problem and tests them for feasibility. Thus, the team iteratively moves toward one or a few potentially feasible solutions. These solutions are refined, elaborated, and tested. How? You create hypotheses and test them.

The following criteria should apply to the hypotheses generated:

- The hypotheses raised must be testable (based on facts, to be answered with right or wrong), precise (what, who, when) and clear (concrete).

- The hypotheses raised should relate to feasibility and profitability and desirability.

- The hypotheses are tested with an „experiment“, where appropriate metrics and criteria make the experiments measurable and assessable in terms of their success.

Once all hypotheses have been confirmed with evidence (facts & data), we have found the right solution and we have developed our value proposition for the products that are loved.

We know the customer job, the customer pains, and the customer gains. We can describe the solution (products & services), know how our solution eliminates the challenges (pain relievers) and delivers value to the customer (gain creators).

This is where the work of the developers and product managers begins, who now must ensure that in the development process – from the technical specification to the finished product – there is no further deviation from the basic idea, that the customer benefits are ultimately achieved as planned.

If this succeeds, a product is created, which has good chances to be loved by the user!

Note: The double diamond is partly used as a design process. Here it is called discovering (divergent – finding the problem / the starting point for a product idea), defining (concretize the idea – convergent), developing (develop product solution – divergent), delivering (in the sense of final test, release, produce and launch – convergent).

| Sources: |

| Lewrick, Link, Leifer: The Design Thinking Playbook (2018) Bland & Osterwalder: Testing Business Ideas (2020) Osterwalder, Pigneur, Bernarda, Smith: Value Proposition Design (2014) www.designcouncil.org.uk |

| Picture source: |

| 1(Title) Clark Tibbs, https://unsplash.com ²Alibaba, ³Pinterest, 4freehander.de |